John Wesley’s Creation Theology

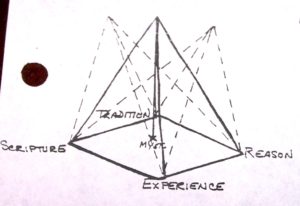

The four sources of authority for John Wesley – Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience – have long been an important decision-making guideline for me. As a lifelong camper, I’ve tended to see this “quadrilateral” as the four corners of a tent with the crossbar of Jesus Christ holding them together in the center. Some people’s “tents” lean a little more in one direction than another (C.S. Lewis influenced more by reason and tradition, for example), but all hold strong in storms, and many people fit inside the tent.

When I read Sharon Delgado’s book, Love in a Time of Climate Change, I found so much richness in h er research and personal application to John Wesley’s creation theology that I wanted to share it here with you.

er research and personal application to John Wesley’s creation theology that I wanted to share it here with you.

Scripture – “The whole scope and tenor of Scripture affirms the centrality of compassion and justice as expressions of divine love,” says Delgado (p. 107). She begins with Wesley’s oft-quoted line, “I allow no other rule, whether of faith or practice, than the Holy Scriptures” (34). But then she notes Wesley’s advocacy of using reason to interpret an individual passage in the light of the whole of Scripture. “The Spirit of God not only once inspired those who wrote it,” said Wesley, “but continually inspires, supernaturally assists, those that read it with earnest prayer.”

Tradition – We can’t just superimpose the viewpoints of historical persons on our current circumstances, Delgado says, but we can learn from their historical view (37). Focusing on John Wesley’s contributions, she highlights his unique understanding of God’s presence in creation, and Wesley’s concept of social holiness: living in a way that considers the effects on others of our lifestyle and actions (126). We can also follow Wesley’s open-minded approach to theology, science, and social issues, as well as his insistence on love as basic to “true religion” (37).

Reason – Wesley invited us to use our common sense and powers of critical thinking. “Science informed Wesley’s understanding of creation,” the book says. For example, he accepted Copernicus’ view of the universe, directly challenging the ancient worldview of the earth at the center. Wesley also wrote a two-volume “compendium of natural philosophy” that brought natural science and theological commentary together.

Experience – Personally knowing God, not knowing about God, is the one source of authority that Wesley added to his Anglican tradition. “This ‘heart religion’ comes about through inner experience; through direct knowledge given by God to the soul,” Delgado says (39). In Wesley’s sermon on “The Witness of the Spirit I,” Wesley said, “The  testimony of the Spirit is an inward impression on the soul, whereby the Spirit of God directly witnesses to my spirit that I am a child of God, that I, even I, am reconciled to God” (65f.). This assurance of God’s forgiveness and love is the very foundation of faith (39).

testimony of the Spirit is an inward impression on the soul, whereby the Spirit of God directly witnesses to my spirit that I am a child of God, that I, even I, am reconciled to God” (65f.). This assurance of God’s forgiveness and love is the very foundation of faith (39).

The book’s description of these four sources of authority is particularly helpful as it introduces Wesley’s “amazingly rich and varied” creation theology (what had previously been entirely unknown to me). Defining grace as “God’s love at work in the world” (63), it considers all of creation as the object of sanctification, and presents multiple aspects from Wesley’s sermon, “General Deliverance.” Delgado unpacks Romans 8:18-26 as embracing the earth and all creatures from the vantage points of Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. Offering us a “New Creation Story” (78ff.), she announces that “grace works with, in, and through us to help move creation toward renewal” (67).

Love in a Time of Climate Change is well worth reading from many angles, and I heartily commend it to you!

Your partner in ministry,

Betsy Schwarzentraub

See also: Love in a Time of Climate Change by Sharon Delgado